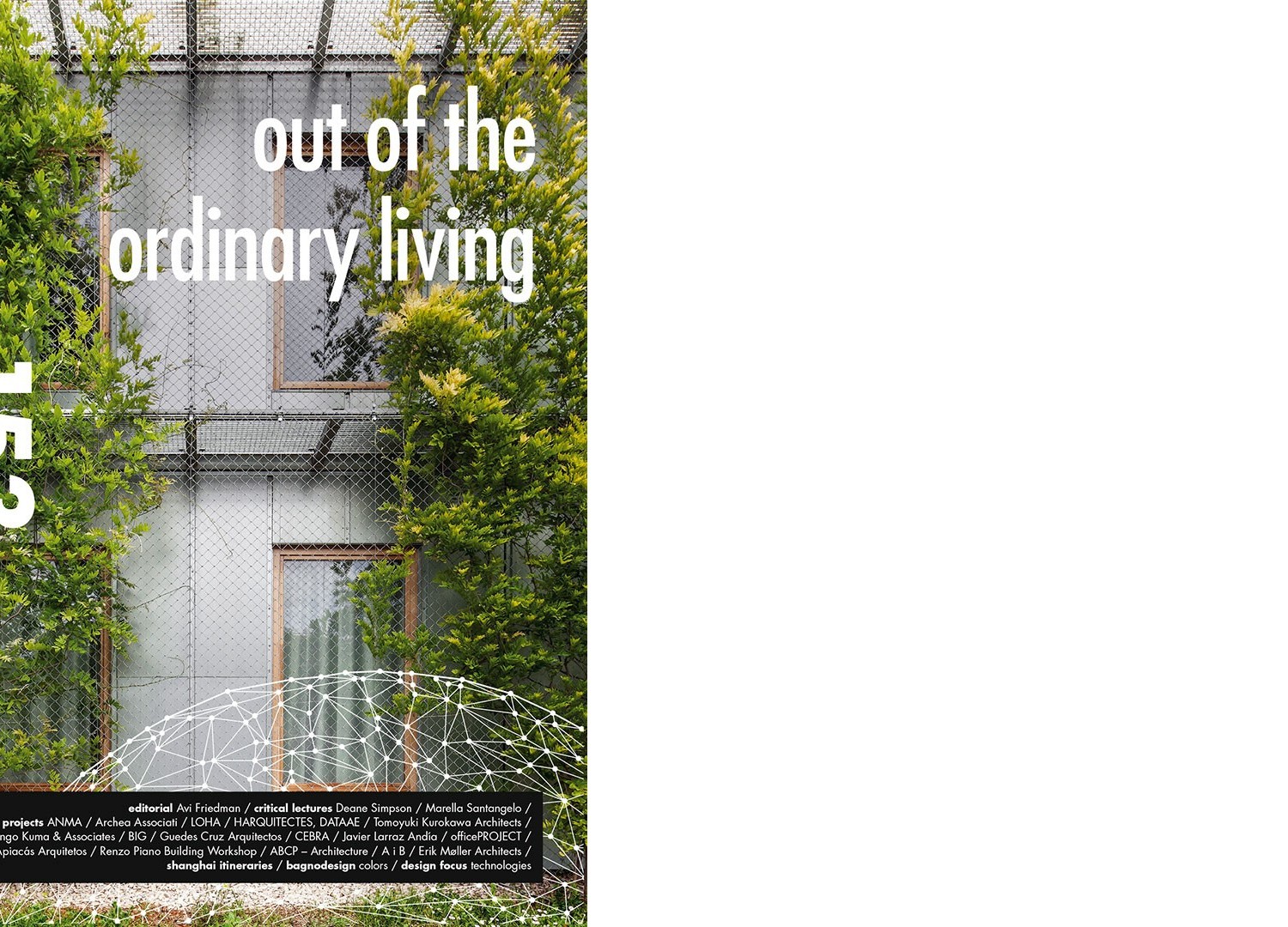

International magazine of architecture and project design july/august 2017

The landscape of inhabiting

Architecture is art. In other words, it is that discipline in the arts that uses technology and other tools to build places of living. Architecture, Art and Abitare (Inhabiting) incidentally, but in my view intentionally, constitute a rhetorical figure, that of alliteration, which is the basis of the design process where many of the elements themselves, whether columns, pillars, or walls, are repeated in various ways to achieve a work. The work, according to some scholars – how can we not recall the battles of Bruno Zevi – becomes Architecture only if it is able to contain a useful space for human activities, that is, in which to live. And still we can see that the three key words – Art, Architecture, Abitare – begin with the letter “A”, an obvious ideogram that depicts a roof, a house, a primitive hut, an observation which Marc-Antoine Laugier was to point out in the eighteenth century. Why this painstaking and complicated quest for the natural archetype? Because in order to belong to the arts and to win over beauty, the sublime, a concept that lasted until at least the end of the nineteenth century, architecture, on a par with the other arts, had to be built on the image and resemblance of nature which for the architect is precisely a place with a roof in which to live. Later, that roof was to become flat or even with a garden, according to one of the famous LeCorbuserian dictates, but the sense and value of architecture remains indissolubly tied to the role of living. However, human activities are manifold, we could even say infinite in terms of methods and models, and investigating such methods and models is not a challenge, a divertissement, but precise and constant research that makes architecture also scientific knowledge where, without the rigour of the systematic, it becomes important to consider existing species and subspecies in terms of evolution, including their characteristics of genre, family, order and class. In a hypothetical tree scheme, where the house forms the main trunk, there are infinite variants each of which has different features, typologically and hence strategically studied to respond to the various ways of living that depend on the geographical, social and economic conditions of each inhabitant. But before these factors, they depend on the chosen genre: the home to inhabit, home to study, home to pray, home to have fun, and so forth. From this we can deduce how complex and articulated the architect’s way of working is, constantly in precarious equilibrium between art and science, but also between literature, theatre and practical knowledge, that of building; a kind of transversality that brings us back to humanism, to the idea of the universal artist, a “Leonardesque” figure today totally out of fashion in the contemporary context of extreme specialisations, yet so unattainable and fascinating as to make us insatiably persist in our quest for a remote and arduous oneiric way of working. Continuing to study, research, catalogue, modify and interpret is an inevitable task. Investigating beyond form, appearance, calligraphy, soul, structure and substance of the houses/things that we design constitutes the barrier adrift from the uniformity and speculative logic of the market. An economic sector, real estate, which has very little of “real“ and more and more often destroys and mortifies the landscape, making the act of inhabiting sad and uniform, which fortunately remains a general need that is, inevitably, carried out according to the individual. If we comprehend these reasons, we understand why it still makes sense and is useful to continue producing a magazine, to investigate the sense of our work, to exist and to insist on thinking as architects. Because architecture is the art of living.

Marco Casamonti

Download cover

Download table of contents

Download introduction of Marco Casamonti

Download “Colle Loreto – Archea Associati”